Before there really was such a thing as a high-concept movie, in 1967 Warner Bros. released this doozy of a nail-biter whose intriguingly unorthodox casting and high-concept thriller premise resulted in lines around the block and a boxoffice ranking as 16th highest-grossing film of the year. The film:

Wait Until Dark. The casting: All the heavies are played by actors best known for comedy roles. The concept: Somebody wants to kill Holly Golightly!

![]() |

| Audrey Hepburn as Susy Hendrix |

![]() |

| Alan Arkin as Harry Roat, Jr. |

![]() |

| Richard Crenna as Mike Talman |

![]() |

| Jack Weston as Sgt. Carlino |

![]() |

| Efrem Zimbalist Jr. as Sam Hendrix |

As if drawn to the theater for the collective purpose of forming a militia in her defense, 60s audiences

—long-accustomed to spending a pleasant evening being charmed by the winsome, doe-eyed, Belgian gamine of

Sabrina and

Breakfast at Tiffany's—turned out in droves to witness Hepburn as a defenseless blind woman tormented by a gang of sleazy, drug-dealing, New York thugs. The Old-Hollywood zeitgeist had shifted in a big way! And if you don’t think placing cinema’s much-beloved eternal ingénue within harm’s way is a concept both incendiary and controversial, you must have missed the 2010 Internet war raged against Emma Thompson when she dared utter but a few disparaging remarks about everyone’s favorite sylphlike waif.

Then writing a remake of

My Fair Lady, Thompson (ignorant or indifferent to the fact that, at least on this side of the pond, anyone trash-talking Audrey Hepburn is just begging for a major ass-whippin’) drew the heated ire of millions when she expressed the opinion that Hepburn couldn't sing and “Can’t really act.” There's no reason to believe there's any connection between this public outcry and the fact that Thompson's

My Fair Lady reup has seemed to hit a snag, but if there’s one thing Audrey Hepburn elicits from movie fans, it’s the near-unanimous desire to shield and protect her. A quality exploited to entertainingly nerve-racking effect in

Wait Until Dark.

![]() |

What did they want with her?

Poster art for Wait Until Dark prominently featured the image of a screaming Audrey Hepburn accompanied by the above tagline. Yikes! |

From the moment I first saw her in

Roman Holiday, I've always thought of Audrey Hepburn’s screen persona as akin to that of a butterfly. A creature so exquisitely fragile and beautiful that you couldn't bear seeing harm come to it. Sure, Hepburn was drolly menaced in

Charade, and, most certainly, pairing the then 27-year-old Hepburn with 57-year-old Fred Astaire in

Funny Face constitutes some form of romantic terrorism; but for the most part, Audrey Hepburn has always seemed to me to be a woman far too adorable and classy for anybody to mess with.

That being said, I don’t number myself among her fans who would have been happy to have seen her continue along the path of taking on the same role in film after film. When Hepburn made the heist comedy,

How to Steal a Million, in 1966, she was 36 years old, a wife and mother, yet still playing the sort of girlish role she virtually trademarked in the 50s. While that comedy revealed Hepburn in fine form and as radiant as ever, it was nevertheless becoming clear that in a world making way for Barbarella, Bonnie Parker, and Myra Breckinridge; it was high time for the Cinderella pixie image to be laid to rest.

Taking on the role of the tormented blind woman in

Wait Until Dark was a concentrated effort on Hepburn's part to broaden her range and break the mold of her ingénue image. Earlier that same year Hepburn appeared to spectacular effect opposite Albert Finney in Stanley Donen’s bittersweet look at a troubled marriage,

Two for the Road. Giving perhaps the most nuanced, adult performance of her career, Hepburn in modern mode revealed a surprising depth of emotional maturity that signaled, at least for a time, she might be one of the few Golden Age Hollywood stars able to make the transition to the dressed-down 70s. While

Two for the Road ultimately proved too arty and downbeat for popular tastes,

Wait Until Dark was a resounding boxoffice success and garnered the Oscar-winning actress her fifth Academy Award nomination.

![]() |

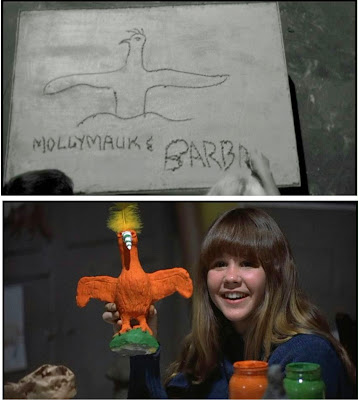

| Wait Until Dark was adapted from the hit 1966 Broadway play by Frederick Knott (Dial M for Murder) which starred Lee Remick in the role that won her a best Actress Tony nomination. Recreating the role she originated on Broadway, actress Julie Harrod (above) portrays Gloria, the bratty but ultimately resourceful upstairs neighbor. |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM:I really love a good thriller. And good thrillers are awfully hard to come by these days. When a suspense thriller succeeds in its objectives to send a chill up my spine, keep me guessing, or, better yet, induce me to spend a restless evening sleeping with all the lights on…well, I’m pretty much putty in its hands and will willingly follow where I’m led.

Wait Until Dark does a marvelous job of duplicating the formula that worked so well for Ira Levin in both

Rosemary’s Baby and

The Stepford Wives--two of my all-time favorite suspense thrillers.

Wait Until Dark takes a vulnerable female character (a woman recently blinded in a car accident, just learning to to adapt to her loss of sight); pits her against an enemy whose degree of malevolence and severity of intent she is slow to recognize (Susy is the unwitting possessor of a heroin-filled doll her tormentors are willing to kill for); and (most importantly) takes the time to develop its characters and methodically build suspense so as best to encourage empathy and audience identification. Simple in structure, yet rare in its ability to sustain tension while providing plenty of nightmare fodder,

Wait Until Dark is one of those scary movies that still packs a punch even after repeat viewings.

![]() |

| When it comes to strict adherence to logic, most psychological thrillers don't hold up to too-close scrutiny. Wait Until Dark is no exception. Plot points and theatrical devices that play well on the stage don't always translate to the hyper-realistic world of motion pictures. But when a thriller is as fast-paced and full of spook-house fun as Wait Until Dark, head-scratchers like the one above (I won't give anything away, you'll have to see the film) won't hit you until long after your pulse has returned to normal and the film has ended. |

PERFORMANCES:

A while back I wrote about how refreshing it was to see Elizabeth Taylor tackle her first suspense thriller with 1973’s

Night Watch. In thinking back to 1967 and my first time seeing Audrey Hepburn’s genre debut in

Wait Until Dark, the word that comes to mind is traumatizing. Yes, it was quite the shock seeing MY Audrey Hepburn keeping such uncouth company and being treated so loutishly in a film without benefit of a Cary Grant or Givenchy frock for consolation. Like everybody else, I had fallen in love with Audrey Hepburn’s frail vulnerability in

Funny Face and

My Fair Lady, so seeing her brutalized for a good 90 minutes was a good deal more than I was ready for at the tender age of ten.

![]() |

| Javier Bardem's creepy psychopath of No Country for Old Men owes perhaps a nod to Alan Arkin's equally tonsorially-challenged, undies-sniffing nutjob in Wait Until Dark. |

Over the years, my shock over Hepburn’s deviation from type has given way to an appreciation of the skill of her performance here. Actors never seem to be given the proper credit for the realistic conveyance of fear and anxiety, yet I can't think of a single thriller or horror film that has ever worked for me if the lead is unable to convince me that he/she is in genuine fear for their life. Audrey Hepburn delves deep into her character and unearths not only mounting apprehension at her circumstances, but taps into the frustration and helplessness the character feels when confronted with the obstacles her lack of sight places on her means and options of escape and self-defense. Hepburn's is the emotional linchpin to the entire movie, and she is incredibly affecting and sympathetic. Without benefit of those expressive eyes of hers (she somehow allows them to go blank, yet finds ways to have all manner of complex emotions play out over her face and through her body language) Hepburn keeps us locked within the reality of the film. Even when the plot takes a few turns into the improbable (once again, my lips are sealed!).

![]() |

| 60's model Samantha Jones (yes, Sex and the City fans, there IS a real one) plays Lisa, the inadvertent catalyst for all the trouble that erupts in Wait Until Dark. Jones' fabulously 60s big-hair,big-fur, slightly cheap glamour seems to have been borrowed by Barbra Streisand's prostitute ("I may be a prostitute, but I'm not promiscuous!") in 1970s The Owl and the Pussycat. |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY:

Having been born too late to experience the mayhem attendant the release of Alfred Hitchcock's

Psycho, with that famed shower scene, I'm therefore thrilled to have had the experience of actually seeing

Wait Until Dark during its original theatrical run, when exhibitors turned out all of the theater lights during the film's final eight minutes. Jesus H. Christ! Such a thunderous chorus of screams I'd never heard before in my life! My older sister practically kicked the seat in front of her free of its moorings. At least I think so. I was on the ceiling at the time. Without giving anything away, I'll just say that while that experience has since been duplicated at screenings I've attended of the films

Jaws,

The Omen,

Carrie, and

Alien; it has never been equaled. At least not in my easily-rattled book.

![]() |

I hope William Castle appreciated the irony.

At the exact moment that director William Castle - the great granddad of horror gimmickry - was making a bid for legitimacy with Rosemary's Baby, Wait Until Dark, a major motion picture with an A-list cast, was attracting rave notices and sellout crowds employing a promotional gambit straight out of his B-movie marketing playbook. |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS:

Audrey Hepburn ventured into the damsel-in-distress realm just once more in her career (with this film's director, Terence Young, no less). Unfortunately, it was in the jumbled mess that was

Bloodline (1979). An absolutely dreadful and nonsensical film I've seen, oh, about 7 times. As theatrical thrillers go,

Wait Until Dark is not up there with

Sleuth or

Deathtrap in popularity, but it does get revived now and then. Most recently, a poorly-received 1998 Broadway version with Marisa Tomei and Quentin Tarantino, of all people. In 1982 there was a cable-TV adaptation starring Katherine Ross and Stacy Keach that I actually recall watching, but, perhaps tellingly, I can't remember a single thing about.

![]() |

| As a kid, I only knew Jack Weston from the silly comedies Palm Springs Weekend and The Incredible Mr. Limpett. Richard Crenna I knew from TV sitcoms like Our Miss Brooks and The Real McCoys. Producer Mel Ferrer (Mr. Audrey Hepburn at the time) is credited with casting these two talented actors against type to disconcerting and bone-chilling effect |

When people speak of

Wait Until Dark, it is invariably the Audrey Hepburn version that's referenced, and it's this film to which all subsequent adaptations, like it or not, must be compared. Even when removed from the fun exploitation gimmick of the darkened theater and the novelty of seeing Hepburn in an atypical, non-romantic role,

Wait Until Dark holds up remarkably well. Delivering healthy doses of edge-of-the-seat suspense and jump-out-of-your-seat surprises, it's a solid, well-crafted thriller with a talented cast delivering first-rate performances (save for Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., who just does his usual, bland, Efrem Zimbalist, Jr.thing).

Still, it's Audrey Hepburn

—age 37, inching her way toward adult roles

— who is the real marvel here. Being a movie star of the old order, one whose stock-in-trade has been the projection of her personality upon every role; Hepburn is never fully successful in making us stop thinking at times as if we're watching

Tiffany's Holly Golighty,

Charade's Regina Lampert, or

Roman Holiday's Princess Ann caught up in some Alice-through-the-looking-glass nightmare. But in these days of so-called "movie stars" who scarcely register anything onscreen beyond their own narcissism, I'm afraid I'm going to favor the actress whose sweetly gentle nature comes through in every role she's ever assumed. That's a real and genuine talent, in and of itself.

Copyright © Ken Anderson